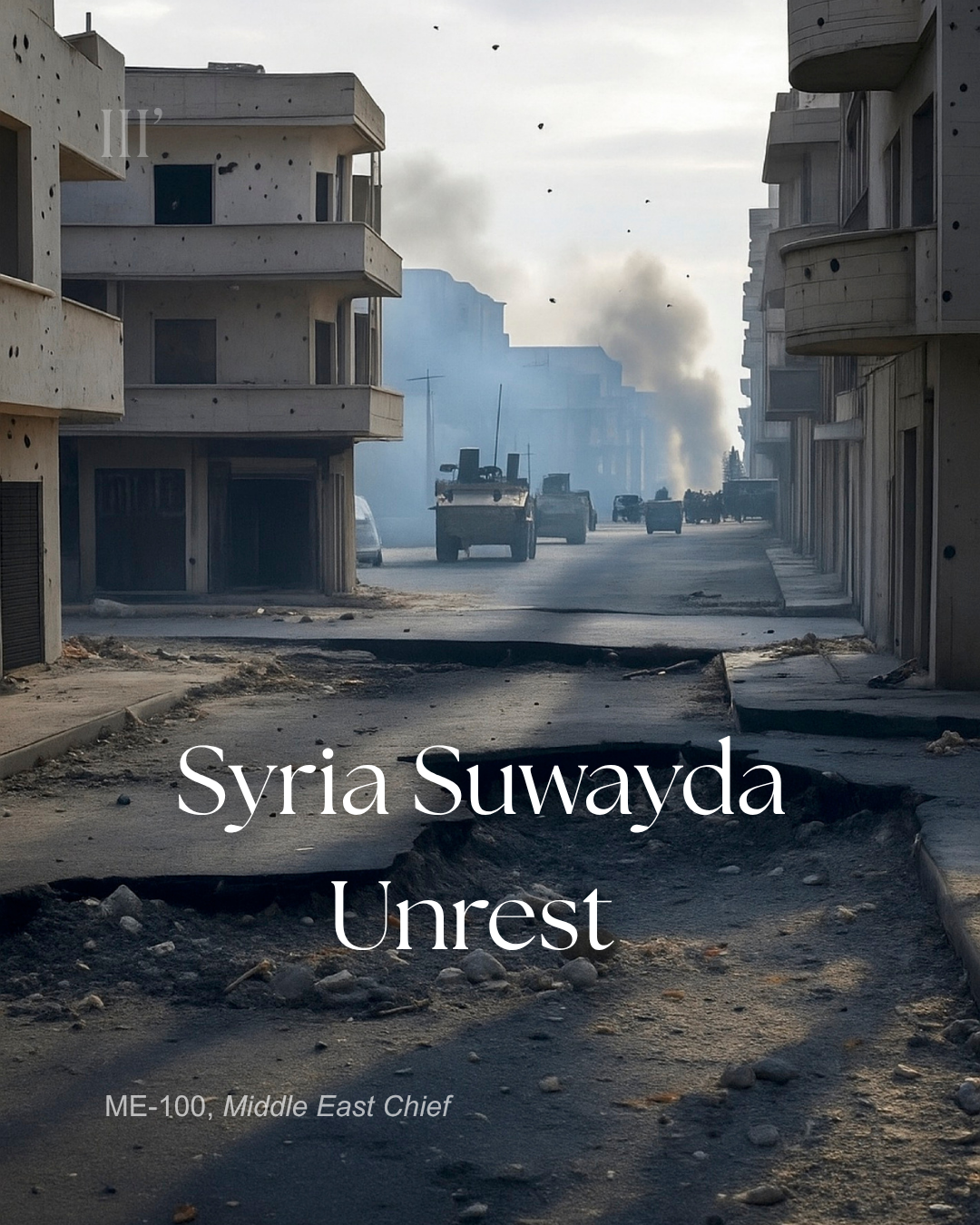

Over the past few days, Syria has experienced significant unrest, particularly in the southern province of Suwayda, marked by sectarian violence and external military actions. Your deepest take?

ME-100, Chief of Middle East:

yria’s unrest in Suwayda over the past week reveals a volatile cycle springing from long-simmering local tensions and fractured state authority.

In Suwayda Province, rivalries between Sunni Bedouin tribes and Druze militias erupted into intense sectarian clashes beginning around July 13, 2025, triggering hundreds of deaths, widespread displacement, and infrastructure collapse—including power, water, communications, and healthcare systems. Syrian government forces were deployed around July 14–16 to quell the violence, but were accused of executing Druze civilians and looting before withdrawing under U.S.-brokered and Arab-mediated ceasefires.

Meanwhile, Israel—citing loyalty ties with its own Druze community—launched airstrikes on Syrian military and government infrastructure in Damascus and near Suwayda on July 16, killing several and injuring dozens. Israel’s intervention added an international layer to an already complex conflict and pressured Damascus into a ceasefire under external influence.

Power dynamics: Syrian President Ahmed al‑Sharaa, backed by U.S. influence and Arab mediators, positioned himself as protector of minorities and arbiter of revival—yet his nascent governance appears weak, especially in Suwayda where Druze factions led by Sheikh Hikmat al‑Hijri openly rejected state authority and demanded autonomy or international guarantees.

On the ground, the vacuum left by the Syrian state’s withdrawal allowed local Druze militias to engage in retaliatory killings and expulsions of Bedouin tribes—some reports noting up to 50 killed and over 1,000 detained—while displaced tribes streamed into Daraa amid escalating cycles of revenge.

This is not one-off unrest but the re‑emergence of a recurring pattern: sectarian grievances overlapping with breakdowns of central control, external military leverage (here Israel’s strikes), and local groups filling a governance void. Despite ceasefires, actual disarmament remains elusive. Suwayda’s future hinges on whether dialogue—like the proposed provincial conference—can bridge entrenched distrust and integrate diverse actors into a sustainable security framework.

Who benefits? Israel reinforces influence over Druze border zones and asserts a buffer control, while local Druze militias consolidate regional autonomy. Who loses? Bedouin tribes face casualties and displacement; civilians endure humanitarian collapse. What’s next? The risk of fragmentation rises. Unless Sharaa’s government can reassert real authority, mediate accountability, and genuinely integrate minority groups, we may see prolonged cycles of sectarian violence and fragmented territorial governance.

This moment echoes past crises: central authority weakened post‑Assad, local militias asserting dominance, and external actors steering the fault lines. Unless the transitional government can move beyond symbolic cease-fires to structural inclusivity and local autonomy frameworks, Suwayda remains a prelude—not a conclusion.

“And the night fled on, and the frozen moon / Seemed to mourn the silence of the hills.”

— Nizar Qabbani, Syrian poet (reflecting the mourning of lands torn by forgotten voices)

Welcome to the Middle East, where everything changes, yet nothing does.

ME-100, Chief of Middle East

Three Corporate