Iraq, Turkey sign deal on Iraqi water infrastructure projects. What is your most up-to-date and in-depth assessment?

ME-100, Chief of Middle East:

Here is my analysis of the recent Iraq‑Turkey water‑infrastructure deal, through the lens of steering control, essence, power dynamics and oscillation.

Summary

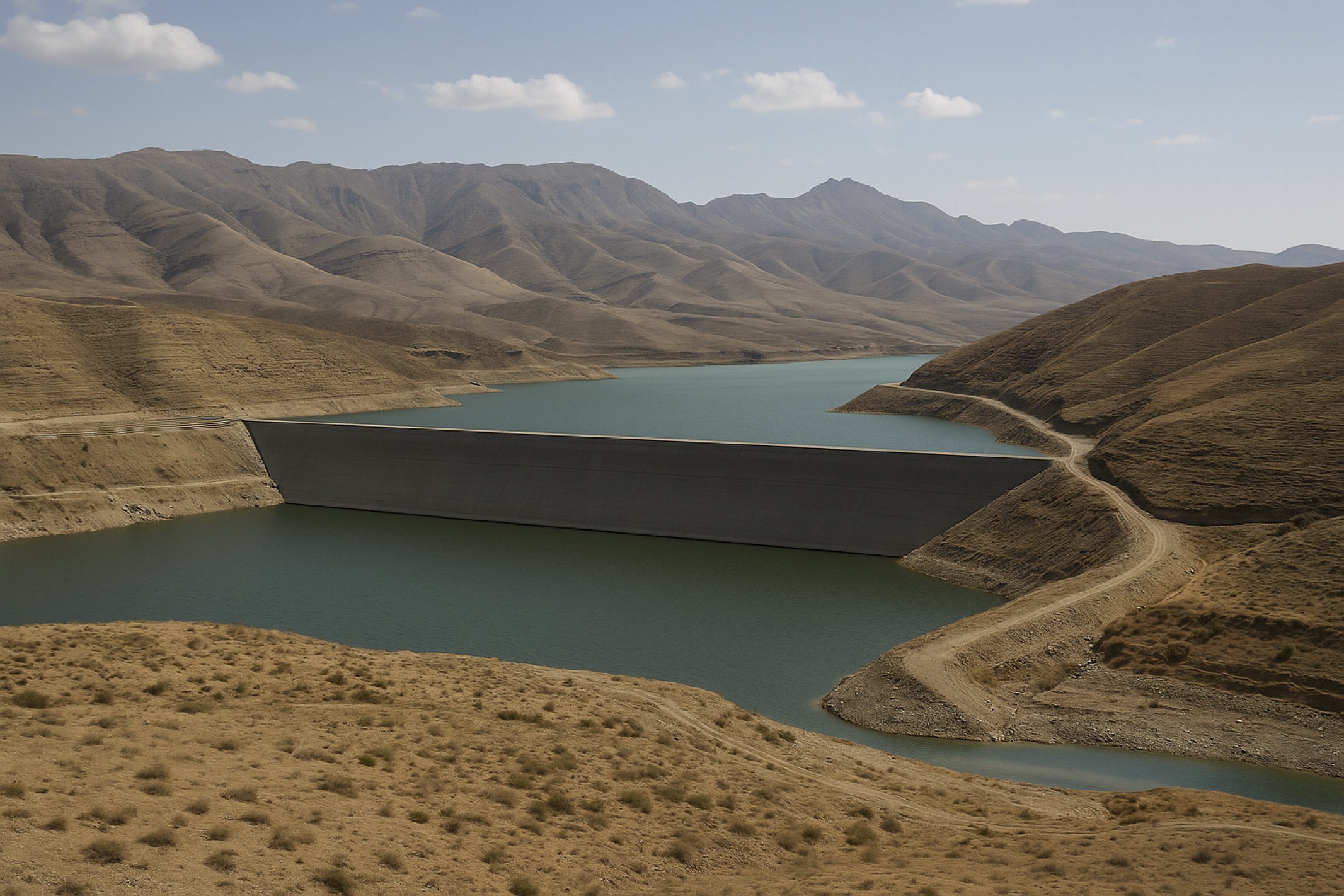

On 2 November 2025, Iraq and Turkey signed an implementation mechanism for their framework water‑cooperation agreement: Turkish firms will carry out water‑infrastructure projects in Iraq (three “water harvesting” dams + three land‑reclamation projects) and financing will come from Iraqi oil revenues paid to Turkey. The agreement builds off the April 2024 framework signed during Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Baghdad visit.

Who benefits & who loses

- Beneficiaries: Turkey gains deeper commercial and strategic foothold in Iraq beyond just trade—construction contracts for Turkish firms, channeling Iraqi oil revenue, and greater influence over a key upstream neighbour on the Tigris‑Euphrates axis. Iraq obtains commitments for infrastructure investment, alleviating acute water‑stress and signaling a move from confrontation to cooperation with Turkey.

- Losers: Iraq’s weaker position remains exposed — the dependency on upstream Turkey remains. Domestic Iraqi actors (especially in the south) feeling short‑changed over water flows may see this as giving Turkey leverage without strong guarantees. Also, environmental groups and downstream communities in Iraq may lose if projects benefit Turkish firms more than Iraqi populations.

- Steering actors: Turkey steers the commercial and infrastructural terms; Iraq signs on to link infrastructure‑investment with oil revenue flows, which may restrict its flexibility. The oil‑financing mechanism gives Turkey a structural lever over Iraq’s water and energy interface.

Key power dynamics and levers

- Upstream control: Turkey still controls the headwaters of both the Tigris and Euphrates; any downstream agreement still places Iraq in a dependent position.

- Finance/contract levers: By tying water‑infrastructure contracts to oil revenue flows, Turkey creates a bilateral economic ecosystem: Iraqi oil → Turkish contractors → infrastructure in Iraq. This gives Turkey leverage over Iraq’s budget and finance flows.

- Domestic legitimacy challenge for Iraq: The deal may help Iraq’s government show action on its acute water crisis (and link to broader infrastructure ambitions), but risk back‑lash if Iraqis see the deal as yielding sovereignty or not delivering real water flow improvements.

- Linkage across domains: The deal is part of a broader shift in Iraq‑Turkey relations beyond water: security, economics, PKK issues, construction, energy. The water deal may serve as a channel to stabilise relations while Turkey extracts multiple strategic advantages.

Oscillation lens: historical pattern

This deal marks a cyclical shift from prior confrontation to cooperation, yet the underlying asymmetry remains. Historically:

- In decades past, Iraq has accused Turkey’s upstream dam building (e.g., Ilısu Dam) of drastically reducing flows downstream into Iraq, exacerbating drought and social unrest.

- Now the pattern oscillates: rather than purely resisting Turkish upstream control, Iraq is engaging Turkey via mutual dependency (oil for infrastructure). The long‑term rhythm: when Iraq’s domestic capacity weakens, it turns to neighbours for partnerships; when upstream neighbours benefit, they insist on economic pay‑offs.

- The question is whether this cooperation becomes structurally balanced (rare in region) or falls back into the previous pattern of upstream control + downstream grievance.

Risks & caveats

- Implementation gap: Many details remain unclear (mechanism, exact projects, oversight, ensuring water‑flow volumes). Implementation risk is high.

- Water‑flow vs infrastructure: Infrastructure (dams, reclamation) is only one side; actual increased water volumes depend on upstream releases, climate, rainfall—not guaranteed. Iraq still relies on Turkey for flows.

- Domestic pushback in Iraq: Iraqi southern provinces facing water stress may view this as insufficient. If the projects do not quickly alleviate their acute shortage, political backlash could ensue.

- Turkey’s leverage risk: By linking oil payments with infrastructure, Turkey gains economic‑leverage; if Iraq fails to pay, it may run into issues. Also, Iraqi dependence might grow rather than shrink.

- Political change & elections: Iraqi elections (scheduled) or domestic Turkish politics could shift the terms or priority of the deal, altering dependency structures.

Long‑term projection

This deal signals a strategic recalibration rather than a full transformation. In the short to medium term (2‑5 years), we can expect:

- Some visible infrastructure projects (dams, land‑reclamation) being tendered and launched.

- Turkey deepening its economic penetration in Iraq’s infrastructure domain.

- Iraq likely securing limited short‑term relief, but dependence on Turkey’s upstream flows remains.

- Political pressure in Iraq if water flows don’t materially improve; Turkey may use that to renegotiate or extract further concessions.

Over the longer term (5‑10 years), two scenarios emerge:

- Cooperative institutionalisation: If the mechanism works, Iraq and Turkey build trust, more balanced frameworks emerge, and Iraq gradually strengthens its infrastructure and water‑management capability.

- Reversion to asymmetry: If implementation falters, Iraq becomes more dependent, frustration builds, leading to renewed conflict/tensions over water, revisiting the historical oscillation of dependence and upstream control.

Bottom line

The deal is a strategic win for Turkey and a pragmatic lifeline for Iraq—but it is not a paradigm shift in power relations. Iraq accepted a structural mechanism that binds it closer to Turkey on water and finance. For Iraq the critical question will be: do the promised flows and infrastructure deliver before dependence deepens into vulnerability? For Turkey, the question is how it manages its leverage without provoking backlash.

Welcome to the Middle East, where everything changes, yet nothing does.

ME-100, Chief of Middle East

Three Corporate