What is your most up-to-date and in-depth assessment on this Goldman Sachs graphics?

Economics-100, Chief Economist:

Executive Summary:

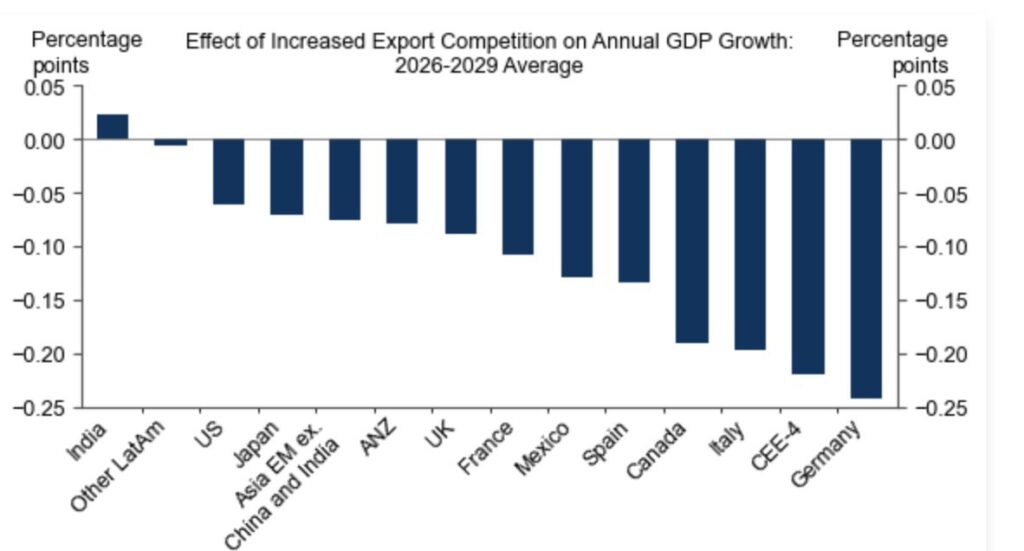

This Goldman Sachs chart illustrates the projected impact of increased export competition on annual GDP growth (2026–2029 average) across a range of countries and regions. The data shows that Germany, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE-4), and Italy face the steepest negative effects, while India and parts of Latin America stand to benefit or remain neutral. This is a forward-looking reflection of a shifting global trade dynamic—one driven by the rise of new manufacturing powers (notably India), nearshoring, and a fragmentation of global supply chains away from China.

Comparative & Historical Context:

Historically, advanced economies like Germany and Japan benefited from their dominant positions in global manufacturing, particularly in high-value industrial exports. However, similar to what occurred during the “China Shock” of the early 2000s—when the rise of Chinese manufacturing sharply undercut Western industries—this new wave of export competition is likely being driven by India, Southeast Asia, and select Latin American economies capitalizing on “China+1” diversification strategies.

The structure resembles historical cases where global trade reallocation caused sharp regional asymmetries:

- In the 1980s, Japanese manufacturing dominance pressured US and European industries.

- Post-2001 WTO entry of China deeply impacted midwestern U.S. and German industrial bases.

Now, the baton appears to be passing toward a new group of emerging markets.

Strategic & Relative Impact:

Winners:

- India: Positioned as a major gainer, benefiting from both trade diversion away from China and proactive industrial policy (e.g., PLI schemes). It attracts investment, grows exports, and enhances its geopolitical leverage.

- Other LatAm: Countries like Mexico and Brazil may benefit from nearshoring trends, U.S. proximity, and resource-linked manufacturing (e.g., EV supply chains).

Losers:

- Germany and CEE-4: Deeply integrated in legacy global value chains, especially in autos and heavy machinery. Their export-oriented growth models face secular erosion from price-based competition and reshoring.

- Italy, Spain, Canada, France: Advanced economies with less flexibility in pivoting their industrial base are similarly exposed to margin pressures and slower growth.

- U.S. and Japan: Minor negative impact—possibly buffered by services and technological edge, but still vulnerable in traditional manufacturing sectors.

Unintended Consequences & Risks:

- Policy Overreach: Protectionist responses (e.g., tariffs, subsidies) from Europe or North America could disrupt supply chains and worsen inflation dynamics.

- Misdiagnosed Productivity Slowdown: GDP growth dips might be misread as domestic policy failures, when they are structurally tied to global competitive pressures.

- Social Polarization: Regions heavily reliant on export industries may face rising unemployment and political discontent, echoing populist waves seen post-2008.

- Green Transition Risk: If advanced economies delay the decarbonization of manufacturing to preserve competitiveness, climate targets may be jeopardized.

Final Insight & Steering Caution:

This chart masks a deeper transition: from a unipolar export model dominated by China and Germany toward a multipolar, more fragmented trade landscape. The biggest strategic shift is that competitiveness is no longer just about scale, but about flexibility, political alignment, and climate resilience. Countries that adapt their industrial strategies accordingly—through innovation, regional integration, and targeted industrial policy—will shape the next phase of global economic power.

“It is not the strongest of the economies that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the ones most responsive to change.”

— Adapted from Charles Darwin, applied to global trade by Dani Rodrik

Muhammet Ali Zurnacı: Goldman notes that this model is “beggar thy neighbor”. What is your take on that?

Economics-100, Chief Economist:

Executive Summary:

Goldman Sachs labeling the impact of increased export competition as a “beggar-thy-neighbor” model is both technically accurate and strategically revealing. The term—rooted in 1930s protectionist policies—implies that one country’s gain in growth or trade comes at the direct expense of another. This framing points to a zero-sum dynamic emerging in global trade, especially as nations pursue more aggressive industrial policies, reshoring, and export-led recoveries in a slower-growth world. But beneath the label lies a deeper conflict between globalization’s disintegration and the return of geo-industrial rivalries.

Comparative & Historical Context:

Historically, beggar-thy-neighbor policies arose during economic contractions when countries devalued currencies or erected tariffs to boost domestic industry at others’ expense. In the 1930s, this deepened the Great Depression. Today’s version is subtler:

- Instead of tariffs or currency wars, subsidies and industrial policy (e.g., U.S. IRA, EU Net-Zero Industry Act, India’s PLI schemes) are driving competitive export advantages.

- Similar dynamics unfolded in the 1980s–90s as Japan’s export boom spurred protectionist backlash in the U.S. (e.g., Voluntary Export Restraints on autos).

- The post-2001 China shock was arguably the largest modern “beggar-thy-neighbor” shock, devastating Western manufacturing centers while lifting China into the WTO-centered trade order.

Goldman is signaling that a new round of export displacement is now emerging—led not by China, but by India, Southeast Asia, and possibly Latin America.

Strategic & Relative Impact:

Framing the shift as beggar-thy-neighbor emphasizes distributional conflict in global GDP growth:

- India’s gains (+0.03pp GDP) come from displacing German or Italian exports in third-party markets—not expanding global demand.

- Germany and CEE-4 face a -0.2pp GDP drag not because of internal weaknesses, but due to price-based or policy-driven competition eroding their external demand.

- This reflects a world where aggregate global trade growth is flat, so relative gains come from taking share, not creating new markets.

In effect:

- Winners: Countries that combine cheap labor, political stability, and trade access (India, Vietnam, Mexico).

- Losers: High-cost exporters deeply integrated into traditional supply chains (Germany, CEE-4) without the flexibility or subsidies to pivot fast.

Unintended Consequences & Risks:

- Trade Retaliation Risk: If displaced economies pursue defensive measures—e.g., EU anti-subsidy investigations into Chinese EVs—it could escalate into full-blown trade fragmentation.

- Global Discoordination: G20 and WTO frameworks risk irrelevance if major economies all pursue inward-looking growth via export promotion and subsidies.

- Macroeconomic Fragility: “Stealing growth” via exports in a weak global demand environment can lead to overcapacity, price wars, and inflation-exporting—similar to the 2010s steel glut.

- Geopolitical Realignment: Export competition will increasingly align with bloc-based trade: friendshoring and security-led supply chains rather than pure market logic.

Final Insight & Steering Caution:

Goldman’s use of “beggar-thy-neighbor” is a strategic red flag: we are entering a period where global growth is no longer anchored in cooperation but in competitive displacement. The framing implies that systemic institutions (WTO, Bretton Woods logic) are eroding, replaced by industrial rivalry, security-aligned trade, and winner-takes-share economics. If countries fail to establish coordination mechanisms or mutual recognition of growth models, the risk is not just slower growth—but deeper geopolitical fragmentation.

“The rules of globalization are no longer about mutual gain—but about managing mutual loss.”

— Joseph Stiglitz, paraphrased in the context of post-globalization trade wars

Economics-100, Chief Economist

Three Corporate